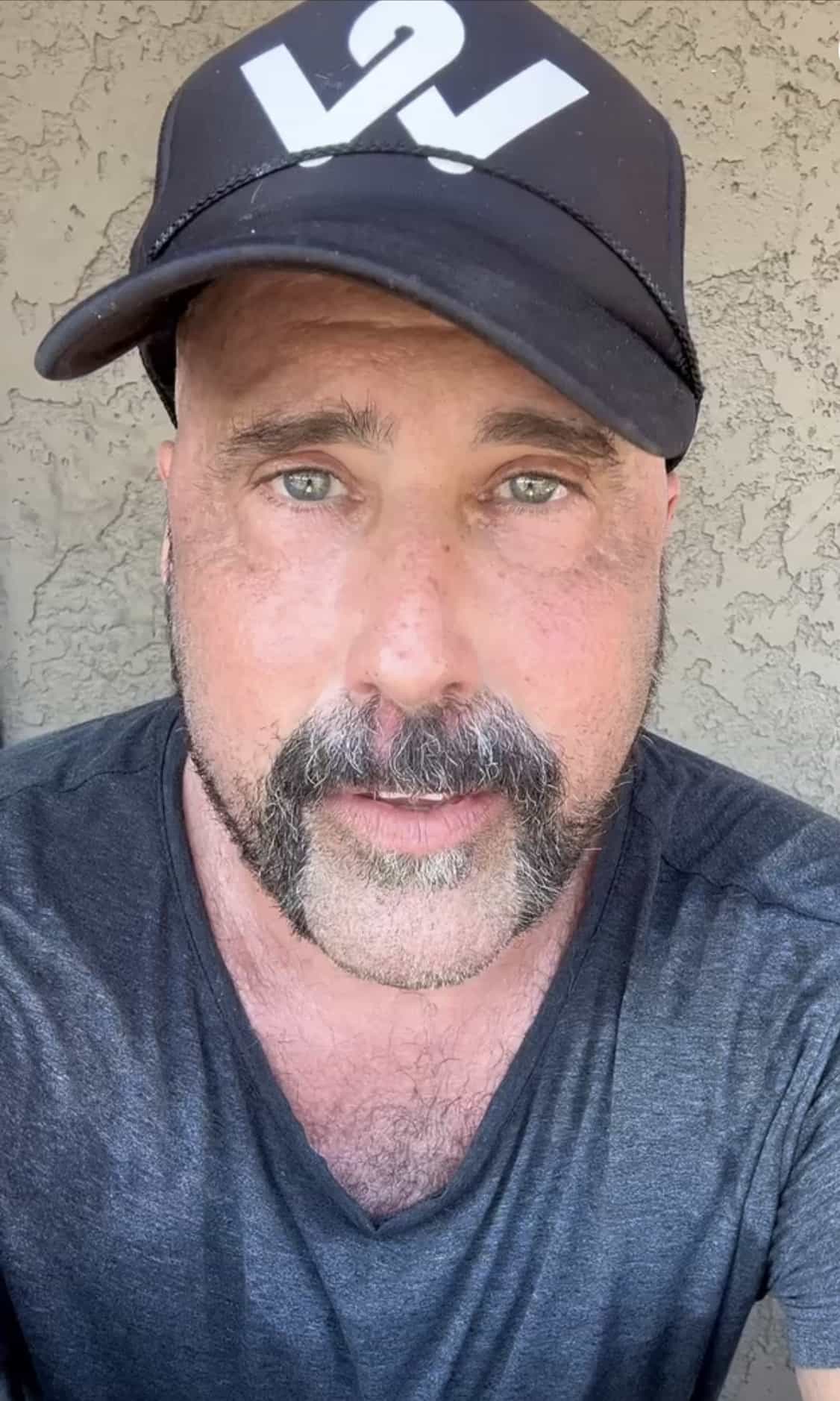

Mathura Hawley aka FAMOUS CANCER INFLUENCER Palm Springs, October 2023

Multiple Myeloma is a brutal cancer. It begins in your plasma, reproduces at a high rate, kicks your immune system like a bully, and then goes out into your body to carve lesions and holes in your spine and any other bones it feels like chewing on. This causes fractures and weakness, and if it happens a few centimeters within in the wrong place, paralysis, kidney failure and a kind of pain you’ve never imagined.

“Mid-2022, Mathura began selflessly contributed his creative talents to WeGotThis.org, helping us shape our branding and craft compelling copy for our upcoming Cancer Gift Registry. Just as we were on the brink of launching the registry, life took an unexpected turn for Mathura when he received his own cancer diagnosis. It became necessary for him to pause his involvement with WGT, focusing entirely on his health and recovery. In the spirit of celebrating his incredible contributions and supporting our cherished friend, we invite you to join us in backing Mathura. If you are able, kindly consider visiting his WeGotThis.org registry, and purchasing an item that speaks to you, and, in a show of solidarity, connect with him on Instagram or TikTok, where you can find him at @famouscancerinfluencer. Your support means the world to us and to Mathura as he navigates this challenging time.” – Elissa

SICK

On January 2nd of this year, I wake up coughing with bronchitis, which I haven’t had since I was a kid. Then pneumonia, my first time. With bacterial and viral infections full-blown, I cough so violently and so many hundreds of times that I begin to spit blood and to lose my breath easily. My back and internal muscles are so traumatized by it that they stop working or send excruciating sciatica down my legs. I can barely walk for four more weeks. During the night I pee into a bucket tucked just under my bed, my left foot and toe working enough to grab the corner and position me as I bend and grab the sideboard. Then one night in March, I sink to the floor clutching my phone while trying to enter 911 before I pass out. In the hospital, tests show my heart has taken a beating from the months of sickness and I am in medical “heart failure,” with a mere 20 percent refraction. One CT scan later, a young doctor I have only met the day before comes into my room as I am exiting the toilet and, while I stand holding my IV pole, gown not fully buttoned, cocks his head and half-whispers, “Heyyy, buddy.” “Yes?” I ask, feeling the forced sincerity and noticing the man in the other bed and his family are now quietly staring at us. “Reviewing your scans, we found many divots around your back and pelvis, and unfortunately that often indicates a cancer called Multiple Myeloma.” The family looks away. “OK,” I say.

I HAVE CANCER

Later that night at home, I fall asleep easily on my own pillows. When I open my eyes the next morning, I remember, then scream out, and begin to sob harder than I ever remember crying. I can’t control it. It comes in waves for an hour or more, and I lose my breath a couple of times and must double over and struggle to get it back.

How did this happen?

Why me?

How long do I have?

How painful will this be?

I’m going to be a “sick person.”

I’ll never have sex again.

I’ll be single for the rest of my life.

Cancer is gross.

I get into my jeep and drive around Palm Springs. It doesn’t feel the same. I can hear my own breathing, but the air, light and sounds feel far away, as if I am looking through plastic wrap. I park near a trail I know, take out my phone and record a video, refraining from tears but staying raw enough to be truthful. How different this is than when my mother told us she had cancer thirty years ago at our family kitchen table. She had known for weeks but had only told my father, not my fiancé and I who were packing to move to New York after college graduation. It’s the only time I have been close to cancer or seen the effects on someone I loved and later, near the end, I would pick her up and carry her like a baby, much like she had once done for me. I take a deep breath, post my video, and drive home. Within minutes my phone blows up, but I don’t respond until later that evening, safely back in my 4-poster bed, sheer curtains pulled around it, with the covers over my head and the AC blasting.

TREATMENT

It takes over a month to see an oncologist, and that is by video only. Begging for appointments, hearing office phones ring unanswered, stopped cold at full voicemail boxes, chasing lost referrals, and explaining over and over who you are to the same people is the first phase, done while you’re most sick, and scared. You have been told there is active cancer in your body, doing damage every single second. When you hear a voice on the other end of a phone schedule you for six weeks away without the slightest acknowledgment that you’re both sick and scared, you want to scream. All at once, with the news you’ve just received, you must simultaneously become an expert with your insurance plan, your finances, tax laws, the shady world of disability, and the sometimes-shameful world of the American healthcare system. To become manipulative is your best bet for making it. Oh – and a reminder – you have cancer. Now the meds.

My first medication comes with a 118-page book of warnings. Mostly it doesn’t want me getting a woman pregnant while taking it, so we can skip that section. In the 1950’s, this drug caused such severe birth defects that its toxicity is legendary. I take it three weeks out of every month. I also get a shot in my arm twice a month and take a handful of steroids every Monday, to soften the blow of it all and miraculously remind me what it would be like if I didn’t have cancer. By Friday of every week the steroids wear off and I get to remember again, just in time for a painful weekend.

Other than nausea that seeps far beyond my stomach and makes me feel like an achy, toxic dump, I begin to get skin infections from the effects of the meds on my immune system. They start as bumps on my forearms, legs, under my arms, or at the base of my testicles. Within two days they grow to golf ball size or spread and burst open. They are so large and painful that they wake me from sleep. I’ve been to urgent care four times and on antibiotics for months, on top of the chemo. Kidneys come next, connected to spinal damage, and it took a few times of involuntarily wetting my pants while cooking an egg to get used to that one, with resolve to carry a long jacket when I leave my apartment to cover any accidents, not facing how odd it will be that I’ll be slipping it on in the 100-degree heat of Palm Springs.

And finally, there should be a new word for chemo-induced fatigue because anyone who has ever used “fatigue” casually in a sentence has never had cancer. With my illness running unchecked, and likely having been active for over a year before my doctor friend cocked his head, I quickly lose twenty-five pounds of muscle and most of my shine. “Look,” I say to my friend Amanda in a video message, “I’m a cancer patient.” For the last decade I’ve been a six-morning-a-week gym guy, who walked, hiked, and loved being outdoors. Having to skip more than a few days for a cold has always been mentally stressful, as I have done so much work on body image and dysmorphia caused by childhood abuse and weight struggles. By the end of January’s pneumonia and the beginning of February’s muscle paralysis, I must face that I am not going back right away. But I have no idea then that by May I will be hooked to an IV pole, that by August my back will be fractured, and that by October there will be little-to-no muscle left on me. The steroids give me a chipmunk face. The water and weight gain has created a roll that hangs over my shorts, pushing them down. Skin hangs at the top of my arm where muscle once filled it. My pride of accomplishment, my show of empowerment, the more obvious hard-fought link to my gay male identity, is gone.

TEAM

Last year I began to help a friend-of-a-friend, a 35-year-old woman in LA with stage 4 metastatic breast cancer who was creating the first non-profit gift registry for cancer patients and their supporters called wegotthis.org. I volunteered branding and copy advice and watched it grow quickly from just a great idea to an inspiring website and gift registry. Nine months in came my own diagnosis, and the irony of that isn’t lost on her or the group. The joke is that I am that dedicated when I join a team. The reality is, being a part of it for so long has not only softened the word “cancer” for me, but Elissa (the founder) and everyone around her has given me love, advice and support I would never have had on my own, mostly alone in my apartment in Palm Springs, watching life begin to go by outside my window.

Friends fall into three groups, and there’s no predicting where anyone will fall until they do: The ones that step forward and become part of your everyday texts, calls or care; the ones that hover, read, and add a heart to your social posts with the occasional check-in and reminder they care; the ghosts. I cherish the first, appreciate the second, and forgive the third. Cancer is sort of like the original AIDS of today — you’re scared of getting it, you don’t want to be close to anyone that has it to be reminded of it, or you’ve known someone with it and it’s too much to go through it again. The truth is, cancer today is different than cancer was even 10 years ago, but I get you. My friend Amanda is my daily touchstone, with a spreadsheet of my meds and responses of acknowledgment, information, ideas, and love. We find that voice messages are our way, and if you saw the lines of blue that flow down our text chains, you would think she has me hooked to a heart monitor. Wait, maybe she does – I’ll ask her in thirty seconds. My friend, Chet, is my other daily check-in godsend, an invaluable reminder of the insanity, the humor, and the reality of my own gay experience.

COMMUNITY

As the Gilda Radner saying goes, “Cancer is a membership in an elite club I’d rather not belong to.” I already have a TikTok following with a couple of viral videos about storytelling and a cult-followed gay podcast. Do I want to be public about something as unsexy as cancer? I think not, until I enter, or am shoved, down the path of cancer patient and all the Fellini that comes with it. I search #cancersucks and fcancer and around those hashtags is waaaay more kick-ass attitude about this disease than I would have thought. People, mostly women, are not having it and are advocating, speaking up, out and about themselves during what they often reject as their “journey,” and deem more their “experience,” the one nobody wants. My people?

I decide this cancer “experience” needs poking fun of. It’s how I see things anyway, and maybe I can shine a little light…right into its eyes. I make up a ridiculous character that would never exist (well, never say never) called @FamousCancerInfluencer as if there could be a person who has cancer just as superficially “in it,” as anyone who is paid to unwrap products on camera for a living or gives advice they

may not be qualified to give. You know… social media.

I post a few videos making fun of what happens to your body when you start taking chemotherapy drugs, how to pronounce them, dropping things from neuropathy, demanding a cancer discount at stores, what’s now in your CVS bag, using google for medical advice, the stress of making appointments, and others. Are these things that happen to us funny? Hell, no. Not until we call them out and shake them up a little. And hopefully doing that with a little of the theater major I am (and always will be – it’s one thing that’s not curable).

I add more serious thoughts, health updates, and stories. The response is overwhelming. Do not underestimate the power of shared experience. I learn more about not only my own kind of cancer but many other kinds, I connect with more beautiful, scared, scarred, exhausted, driven, smart, suffering humans than I have ever met in my life. We listen, advise, refer, cheer, console, listen some more, and show up for each other in ways you can’t imagine. Unless you’re in the Club I mentioned. If so, pull up a chair. If you have Multiple Myeloma, then you’re going to want to stand.

IDENTITY

This cancer always comes back, although with new drugs and stem cell treatments, it’s on the list that may change from “terminal” to “chronic,” and when you have the chance to change “terminal” to “anything but terminal,” you run with it. Where I am now may be called remission, when the cancer is no longer wreaking havoc, but it’s becoming the worst part of it all, with spinal and bone damage causing numbness, pain and the shutdown of my legs, making me unable to sit for long or to walk far. This is terrifying. My greatest fear isn’t cancer – it’s loss of mobility. I’m just being honest. Still on chemo, I struggle each day to move. I sometimes use a foldable cane in public now, and my handicap tag is ordered for the jeep. I’m getting a new MRI this week, and meeting with a surgeon. I’m waiting on my disability appeal, and my savings is gone. Who plans for this?

How long will remission last?

Am I disabled?

Will I ever walk normally again?

Is this the body I’m stuck with?

Will I ever go on a date again?

Is this what I will die from?

Gay Pride happens in two weeks in Palm Springs, right around the corner from where I live. I doubt I will go. It’s hard to walk, sit or stand and I’m not steady enough on my feet to chance a crowd. Even if I could get my head around looking bloated from steroids with a roll hanging over my shorts, I’m not sure I want my cancer to define who I am when someone says, “Tell me about yourself.”

Or maybe I do. Or maybe I’ll go. You never know one day to the next with cancer. What I am sure of is that, in just a few minutes, I’m going to make a video on being a CANcer vs. a CANTcer. That should make you laugh.

Mathura Hawley

Palm Springs, October 2023